The economy never really recovered from the financial crisis of 2007-2008. The recession it precipitated – as many know from first hand experience – was the longest and most devastating since the Great Depression. While we’ve been endlessly assured that the recklessness and greed responsible were dealt with, in reality only a few very specific forms of malfeasance were addressed. The solutions presented at the time, paired with the problems that went unaddressed, now underlie what a casual observer might think is a looming COVID-19 (coronavirus) recession.

If you’ll bear with a tortured analogy, as we currently understand it coronavirus is not an especially deadly virus for the young and healthy, but is exceptionally dangerous for those with compromised immune systems and pre-existing risk factors. Precipitous stock market drops in response to the spread of SARS, Ebola, and Zika tell us that investors are just as sensitive and prone to panic as anyone, and a weak economy is far more susceptible to illness than a strong one.

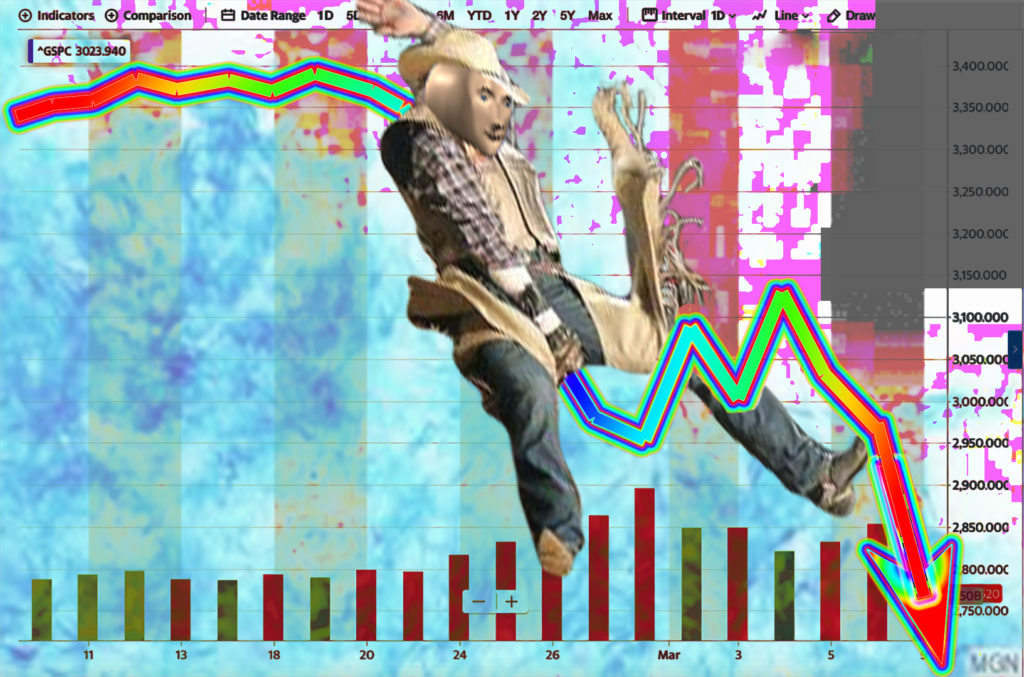

As you can see from the graphs, after the market dropped in response to the aforementioned epidemics, it quickly recovered creating a V shaped line.

But there are substantial differences between the market shocks associated with past outbreaks and coronavirus both in the nature of the emerging pandemic itself, and the current state of the global economy. The V shaped recovery after those epidemics indicate a reflexive fear response. Once investors had time to take in and analyze the information it was clear the viruses would not cause the sort of pandemic that would dramatically harm global commerce. Outside of temporary shifts within specific commodities and industries, the economy at large wouldn’t be greatly affected.

Coronavirus, though, is different. In a short period it has infected more people than SARS or Ebola, and while research into the virus is still ramping up, it’s shuttered vast swathes of productive industry in China and will begin shutting down already sluggish industry around the world as it spreads.

Regardless the specific nature of the coronavirus outbreak the responses are shaping the economic impact, and quarantines outside of China will only make those impacts more pronounced.

Northern Italy is the site of Europe’s largest coronavirus outbreak thus far. Last week, the Italian government quarantined Lombardy and 14 other provinces. An area home to the cities of Milan, Venice, upwards of 16 million people, and the second largest concentration of industrial infrastructure in Europe. Italy’s industrial heartland was already struggling with anemic growth through the end of 2019, and after a slight bounce due to decreased Chinese competition at the outset of the coronavirus pandemic, is now likely to face a major shock of its own.

At this point I’ve established this outbreak is affecting the global economy differently than those that preceded it, but you’re probably wondering what long-term difference it will make. After all, even pandemics eventually peter out, and industry reopens.

The answer lies in the response to the last financial crisis.

As most people remember all too well, the US government’s response was to bail out the banks. People who didn’t and don’t follow excessively boring economic details might not be aware just what shape that took.

Aside from buying up otherwise unsellable “toxic assets” at a significantly higher price than they were worth, thus socialising much of the bank’s losses, they were also offered loans at interest rates approaching 0. Essentially, banks and some insurers were allowed to borrow obscene amounts of money practically for free. This amounted to subsidizing the companies to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars.

After the immediate crisis had subsided these two policies – low interest rates and Quantitative Easing (the FED purchasing assets from business) – were continued. This is an important and defining departure from the past. Since the beginning of the neo-liberal era in the US, starting with the Volcker Shock where interest rates were raised massively, the Federal Reserve has been most concerned with keeping inflation low. Historically that has meant keeping interest rates (cost of borrowing) as high as possible without impeding growth for industry or capital while having no regard to the impact on the population at large. Any time the economy started “overheating”, signalling higher inflation, the FED would raise interest rates in response.

Prior to the two major recessions caused by the Savings and Loan crisis and the Dot Com collapse you can see the FED raising rates. After those crises began, they were dropped in an effort to restart the struggling economy, and once some growth, and most importantly inflation, had returned they gradually began raising rates again.

This has been the economic tool of the Neoliberal era. With direct government intervention being anathema to market fundamentalists, for years there was No Alternative. Instead, it was let markets run amok in the good times, and prop them up in the bad.

But after the Great Financial Crisis something was different. In spite of the low interest rates and QE purchasing of assets, growth barely returned, and inflation was nowhere to be seen. For some reason, pumping billions of dollars in cheap money into the economy didn’t seem to have the expected outcome. Companies borrowed massively, taking on more debt than any other time in recorded history. At this point thousands of economists and traders screamed into the void “WHERE’S THE INFLATION?”

Well, where is it?

It’s in assets. The explosive growth of the stock market has been fueled by a debt binge wherein people pour money into unprofitable companies’ (that don’t make anything) IPOs, companies taking out loans to fund stock buy-backs thus inflating their share prices, corporate real estate speculation, and every other grift and graft made possible by giving the most greedy and least honest people on the planet access to immense amounts of cheap money.

So when the market began precipitously dropping in recent weeks, yes, coronavirus was the trigger, but the ultimate outcome will not be the fault of a single pandemic. Corporate debt is at its highest level, ever. In the US alone it stands around ~$15 trillion, and that has to be serviced on a regular basis. Interest payments come due, and they don’t care if you don’t have the cash on hand to pay because people aren’t spending money and you can’t make your deliveries because of quarantines. Pay up, or default.

And if you default that hits the balance sheets of the people holding the debt, and maybe they then cannot meet their own debt obligations, but maybe they’ve hedged against your default by purchasing, maybe you remember these, credit default swaps.

The massive amount of heavily indebted (‘leveraged’ in financial parlance) companies combined with the ever growing asset bubble has been at risk of collapsing under its own weight for some time now. The “recovery” after the Great Recession was built upon inflating that bubble, and the reason it will eventually burst is because the reaction to the GR never addressed the underlying problem with the economy at large. It’s the same problem that led to the Volcker shock and the supremacy of monetary policy over fiscal policy at the outset of the neoliberal era. It’s the same problem they tried to solve by slowly squeezing working people like us a little more every time a new crisis emerged.

What is that underlying problem? The same one Marx identified over a century and a half ago: the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. Or, as other more savvy observers online have called it Line Goes Down.

Jean Krill is is the co-editor and co-founder of Zero Balance. His writing navigates the many disparate visions of a radically better future.